A guide I put together for current and future students of Arabic.

Section 1: My philosophical Approach To Learning and Teaching Spoken Arabic

(1) A Hybrid of MSA and Colloquial(s) Can be your Goal:

There is a strong tendency for Arabic as a 2nd language programs to compartmentalize their teaching of spoken versus written. A typical school will offer one course in Colloquial Arabic and then several on formal Modern Standard Arabic.

Practically speaking, they are often treated as two separate and distinct languages. Many a student who has slipped into MSA in Amaya class and Vice Versa has heard this from their teacher:

“Sorry, you can’t say that. Wrong class.”

There are of course some good reasons why it’s taught that way. But I started to question that conventional approach in the years after I finished being a formal student and started traveling around the Middle East for work.

Like many students, I had first studied Arabic in Egypt where I internalized Egyptian. This led to a job in the environmental sector in Saudi Arabia. In the Kingdom, the natural Arabic instinct coming out of my mouth was, logically, Egyptian.

I tried to adjust as much as possible and use Saudi phrases. This was important diplomatically. Yes, it is true, while a foreigner who speaks any Arabic will get some “points” initially, after a certain period of time it would sound odd to keep using Egyptian phrases.

Then the whole process repeated itself. I co-founded a company that – to make a long story short – unexpectedly led to me spending a fair amount of time in Lebanon. Same thing. In Beirut the instinctive Arabic words coming out of my mouth were Saudi.

I was torn. Wasn’t this a cycle that could go on forever? Each time I went to a different country? Hadn’t I finished being an Arabic student? Or would I have to relearn new colloquials over and over?

After much thought, I concluded that it may not be necessary to keep acclimating to each regional version of Arabic. I also began to rethink the practical utility of the dominant academic approach to the Ammaya/Fusha divide.

My thinking was this as a non-native student of Arabic:

I am neither a local, nor am I trying to become a professional linguist. My goal was not to be an “expert” on any specific dialect. It was to communicate at a high-level, in a broad variety of work-related practical situations. Equally important, my goal was to do this anywhere in the Middle East while not knowing in advance where that location might be.

For all of those reasons, while some teachers will hate me for saying this, I tell today’s generation of Arabic students that it is perfectly fine to aim for a spoken hybrid of, say, 60% MSA and 40% one or more dialects. More on this in Strategy 17.

What I think is the Important question:

Does whatever combination of Amaya and MSA you speak, get you the results you want?

If it does, it is no less correct than other views out there. Much more on this later in the post.

(2) Academic Teaching of Spoken: Structure Matters

In my humble opinion, formal academic instruction is less critical for learning spoken Arabic as with Written. Still, good teachers, especially at the early stages, makes a huge difference.

On that note, I strongly recommend International Language Institute in Cairo where I studied several times from 2006 to 2008. There were two unique elements to their approach. First, ILI put together organized and structured books on spoken Arabic. Scenarios with different themes such as:

- dealing with problems at work (10 or so different scenarios)

- planning for a trip to the beach (same variety of contingencies etc)

- how to explain when you are angry with someone (10 scenarios etc)

- various ways to return an item to a store etc etc

The lessons were situational and practical. I walked out of class every day with a clearer, structured, grasp of Ammaya than I walked in with. I felt confident I could turn around and successfully teach that lesson to someone at a level just behind me.

Which is precisely my benchmark for what makes great teaching or training: students or employees who have just learned a lesson should ideally be able to teach it effectively to the next class. My philosophy is that all teachers as a general ideal, should be aiming to potentially teach themselves out of a job, as odd as that might sound.

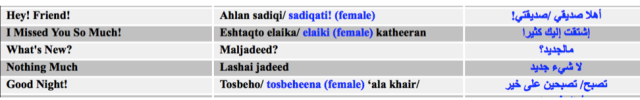

The second “value added” I saw in the ILI approach was that they put the Arabic spoken in print, in Arabic letters. This compares to other Arabic as a 2nd language programs which often transliterate spoken. I am convinced that in teaching colloquial Arabic, the words should be written out.

Why? In practice, the middle column means less to the foreign Arabic student who is studying both written and spoken (although it is true that there is an argument for transliteration for students only aiming at spoken). If students are already studying written, writing spoken Amaya out in Arabic letters creates an economies of scale studying effect:

Finally, one of my sources gives me the following tip on a new textbook with a different approach to teaching Ammaya:

“One approach they should be aware of though is the “Living Arabic” textbook” published by Munther Younes at Cornell. This approach is starts by teaching ‘Ammiyya and then uses that to approach formal Arabic. I’ve heard good things about it. If Cornell or any other university is teaching intensive summer programs around that textbook, that would be a good choice for beginning/lower intermediate students.”

(3) Treat Arabic speaking as a “physical” activity – get in “The Zone”

Too many students spend a year or two in the Arab world and leave without reaching a high-level of spoken Arabic. Why? My theory is that not enough emphasis is put on how learning how to read and write are separate activities.

Speaking is closer to the skills required for a sport, like playing basketball or acting in a play.

Here is what I mean:

First, with speaking the student has to exercise physical parts of their body. They must use various muscles, such as their tongue and throat, not just their brain, which is the only part they are using to read and write.

Most importantly, there is the “performance” aspect.

Let me give you an example. A few years ago I was visiting an international court in Europe. I noticed a woman doing stretches and jumping jacks outside the building. She also seemed to be talking to herself.

Intrigued, I struck up a conversation. I learned that she was an interpreter. This was her routine to get in the right physical and mental mindset for the “perform on the spot” activity of interpretation.

Students aiming to advance their spoken skills should think about getting in the “speaking zone” – similar to what you do if you were preparing to play a sport, like basketball.

Speaking is a physical and social activity. The problem for many study abroad students is that they spend huge amounts of time in the library in highly-introverted solitary settings, focusing on studying written.

They aren’t in “The Physical Zone:”

Could a basketball coach put a player into a game with no warmup and expect them to succeed? Of course not. The same thing is true with languages. Switching from the Written-Mental to the Physical-Spoken mindset can be difficult. It certainly doesn’t happen automatically.

You have to get in “The Zone” to be effective.

Some tips I recommend:

- Have a physical “warmup” – read aloud an Arabic newspaper for 15-30 minutes before you know you will be speaking Arabic. Much more on this later in the post (strategies 18 to 20).

- Get in a social mood, whatever that takes. One thing you can do is watch shows like Seinfeld.

- Try and of the ideas in Strategy 6

(4) The 250 Hour Golden Rule:

When I look back at everyone I know over the past ten years who became high-level Arabic speakers, compared with those who didn’t, every case is explained by this core Golden Rule:

In order to become very good at speaking, the Arabic student must spend 250 hours speaking Arabic in non-classroom situations.

If the student finds a way to generate 250 speaking hours, they will reach a very high level. If not, they don’t. It goes without saying, of course, that 500 hours is better than 250, and 750 is better than 500 and so on.

If you are studying abroad for even one semester, there is no reason you can’t reach 250 hours.

Section 2 will focus on strategies for getting those quality speaking hours.

First though, points 5 and 6 offer my thoughts on the nature of those 250 hours of conversations.

(5) Cherish Good Conversationalists

Cateris Paribus – one hour spent with an engaging conversationalist – someone with an interest in lots of topics who reads lots of books – will be more beneficial to your skills development than several hours with the hardest-core and most one-dimensional “Meathead.”

Therefore, in general, the Arabic student should seek out and spend time talking with great and engaging conversationalists.

(6) If you don’t sometimes feel nervous, you aren’t working hard enough

Still, this point might sound like I am contradicting the previous point. There is a down-side in spending too much time speaking with the Good conversationalists. In practice they are likely to be your Arabic professors or their friends, for example.

Anyone can sit down, at a time of their choosing, with someone whom they are familiar and comfortable with, who knows your speaking patterns and wants to help you, and “perform” Arabic (or any language for that matter).

Whereas the key to really getting good at spoken is making sure a huge portion of your 250 hours take place outside of your comfort zone. You want:

- To be in situations where you nervous

- To be in situations where you are “rattled,” if not embarrassed

That’s perfectly fine. It’s the only way you will get really good.

In fact, my proudest moments as an Arabic student came after I was a formal student. And they occurred precisely because during my days as a student I put myself in hundreds of these types of “stressful” situations.

One time we were in the Eastern Province, deep in the Saudi country side. Two tires blew out on one of the vehicles. There was some other potentially serious technical problem.

As the logistics person for the trip, I drove with one of my team members to find the local mechanic.

It was a stressful situation. We were near the border in the complete middle of nowhere. There had recently been all kinds of warnings about escalated Al-Qaeda threats in this specific area. The Arabic words just came out. Adrenaline took over. I was in “the Zone.” I didn’t even think.

Another time I was driving home from work in Jeddah when an Iranian diplomat (red), upset at my apparent “slow” speed, sideswiped my car trying to get around me (blue).

Here is why this matters Arabic-speaking wise:

While the Iranian guy was 100% at fault, his car had significant cosmetic damage. Mine had basically none. This meant I was potentially vulnerable if it came down to a He-Said, She-Said situation.

Why? Theoretically, the same US driving laws are on the books in the Kingdom. However, the only thing that means for certain is that there is a piece of paper someone that says “these are the driving laws.”

In practice, there isn’t usually a standard system for investigating traffic accidents and apportioning blame in some kind of objective way (at least I never saw one). Therefore, the person who “didn’t cause the accident” is the one who is:

- Better at yelling and/or firmly asserting their case more convincingly to the traffic cop

- Is more liked by the traffic cop for whatever reason

- Some other unknown factor that is impossible to figure out

Again, adrenaline took over.

I was assertive and calmly made my case in Arabic to the Saudi traffic cop. I clearly described everything that happened. He decisively took my side and told me to go home, he’d take care of it from there. My teachers would have been proud.

The Arabic words just came out. I didn’t think. The whole exchange “just happened.”

I reacted and spoke effectively, due to my Arabic learning strategies from my time in Cairo. I had intentionally gone out of my comfort zone enough times while studying, that in practical “Real World” situations I just acted and felt reasonably comfortable doing it.

How can you simulate “outside of your comfort zone” situations?

Here are some ideas:

(1) Take 5 minutes to research terms related to vacuums or some other device that you need to buy. Then Go into a department store, and ask for the pros and cons of the vacuums they have on stock. Only in Arabic. Preferably if there is a line behind you.

(2) Intentionally “get lost” in a neighborhood in the Arabic city you are studying. Then ask for directions in Arabic back to the spot you know and find your way back home. If anyone tries to help you in English, say you are from a country where no one would know the language: Mongolia.

(3) Phone calling — so much of communication is conveyed by body language, seeing each other and that is often a crutch for Arabic students: just call a restaurant to order; call the department store to ask about stuff etc.

(4) Join a gym where you are out of your comfort zone- see point 11

(5) Each person is different — just find any situation where you know you will be more uncomfortable in Arabic – and do it 50x, over and over

Section II: Lifestyle Strategies To Generate 250 Hours

In this section I will reflect on all of the various tactics I recall my fellow students using to get really good at spoken Arabic.

(7) Minimize Contact with Anyone Who Wants To Speak English:

Extremely important. Anywhere you study in the Middle East, you’ll find locals who want to practice speaking English. There are also going to be fun expat communities with interesting people to hang out with. There are no shortage of opportunities to revert to your comfort zone and speak English.

I don’t recommend you be an Immersion Extremist and speak Arabic 24-7 unless you really want to. You don’t need to in order to get good at spoken.

However, you must be disciplined about limiting your English. Consider a business-hours time mindset, where you get eight hours of Arabic in, maybe during the day, and then are more relaxed at night.

Paths to Assimilation :

In the most perfectly fun and interesting world, the foreign Arabic student could find some kind of “Friends”-type living arrangement during their time in the Middle East. In that arrangement they live only with hip locals who conveniently speak not a word of English.

Perhaps such situations exist for students studying Chinese in China, or Spanish in Spain or French in France etc.

Unfortunately for the Arabic student they don’t exist in the Middle East. In conservative Arab cultures (Lebanon included – and all of sects), 99% of people live with their parents until marriage. And the maybe 1% that would live alone are likely to speak very good English.

This means that the foreign Arabic student has to be more creative in finding ways to get the full immersion aspect needed to generate 250 hours. Here are some ideas that I observed or tried during my formal days as an Arabic student:

(8) Live in a Slum (extreme assimilation):

My friend “Chris” took this approach. It was not for me. This was hard-core assimilation, dirt floors, the complete lack of material comfort etc. Although at $20/month, he was saving money on rent.

The results did speak for themselves. Chris’ Egyptian colloquial skills were better than anyone else I knew. However, in today’s political and security climate in most Arab countries, I would generally recommend against this approach without conducting serious research before hand.

(9) Ride the Minibus every day (slightly less extreme assimilation):

My friend “Steve” rode the mini-bus (basically a van that runs along a fixed route) as his primary form of transportation, for the purpose of speaking Arabic.

This is a good idea strictly from the learning-Arabic angle. Theoretically, you are sitting next to someone for a long period of time in a way that naturally facilitates conversation that wouldn’t occur on say, a metro. Again, the results spoke for themselves: Steve’s spoken Arabic skills were very very high.

More importantly – is this is a good idea from a safety perspective?

Yes, on one hand, the student may find themselves sitting next to an Egyptian, who never in a million years would have guessed they’d encounter a fluent American Arabic speaker sitting next to them on a minibus, and have some great conversations.

On the other hand, if you do it enough times these days, the Arabic student is statistically likely to eventually find themselves sitting next to someone as eager to beat up such an American, rather than help them practice their language. Therefore, in today’s Egypt I would say this specific tactic is generally not a good idea. I wouldn’t do it myself.

Middle Ground Assimilation

(10) Live in a Non-Elite Area:

Where the Arabic student chooses to live will effect their ability to generate quality speaking hours. Live in a “nicer” area, your lifestyle will be more comfortable. Perhaps more “fun” depending upon how you define fun.

Whereas if you live in the more “Shaabi” or common areas, it may not be as enjoyable. The tradeoff, however, is you will generate vastly more speaking encounters. You will get to 250 speaking hours faster and more efficiently.

Why? In more upscale neighborhoods like Zamelek or Maadi in Cairo, or Hamra in Beirut, you are just another foreigner. Whereas if you live in places like Sayeda Zeinab, the foreigner is something of a novelty. People will want to talk to you.

Each local city will differ. I do still with caution recommend this strategy in 2016, but only after students do their local research. Talk to your teachers, ask other students who have been at your school for longer. Ask them what they think about which neighborhoods would be good for this strategy.

(11) Join a Gym:

But not just any gym. During one stretch in Cairo I joined two gyms. The first, “Fitness Academy” was solely for exercise. It was your standard US-style gym. During my entire 6 month membership at $90/month, I maybe spoke 15 minutes of Arabic. I was just another foreigner at Fitness Academy.

Gym # 2 was called “Boondock” ($5/month) and was for speaking Arabic. It was located in one of the more blue-collar neighborhoods near Tahrir Square.

Some of the guys there were on steroids. Many of the members were as ripped as Arnold or Rocky if not more. Although it’s also true that as the gym had no cardio equipment I suspect if asked to run 1x around the block, several would pass out.

There was one primary reason for the Arabic student to join. To get the kinds of hours I mention in point 7, especially the unconventional hours discussed in point 6.

(12) Make the Most of Riding in Taxis:

In at least 500 taxi rides in the Middle East, I have easily had 50 quality hours of conversation, probably closer to 100, maybe even more.

Ways you can develop your spoken Arabic skills in a Taxi:

- If you’re going a specific route every day, passing some specific landmark, that’s a natural thing to talk about; ask them a question about it etc etc. Then the next day, ask the same question to a different driver….

- Some issue that every driver will have an opinion on. Talk about it. Almost all will have an opinion on say, soccer teams etc. See point 16 for another suggestion.

That being said, the safety factor is more important in a post-2011 environment. You have to be more careful nowadays.One example is worth mentioning to illustrate new post-Arab Spring realities. (I address the safety issue in great depth in this post)

It took place during the summer of 2013 in Lebanon. I had a meeting in the Central area of East Beirut (Point A) while staying at a hotel in Hamra (point B). This is what I wanted to happen afterwards – quickly find a Taxi and do this:

Unfortunately that didn’t happen. For at least 20 minutes afterwards, even after moving streets multiple times to get a better spot, I was unable to find any taxi.

Not being able to find a taxi isn’t usually the end of the world.

However, this was a very tense time politically in Lebanon.

President Obama seemed to be about to order an attack on the Syrian government. Whatever you think about whether that was a smart idea or not, it meant that there would likely be retaliation by Assad’s allies in Lebanon against US interests inside Lebanon if Syria was attacked.

I don’t look Lebanese.

Eventually, a “Service” (basically a group taxi) stopped. Sure, he’d go to Hamra as soon as we dropped the other passengers off.

Given the tense security climate – this was something I didn’t really want to do. Though with no other options I crossed my fingers and got in.

These “other neighborhoods” weren’t exactly on the way to Hamra. Nor did the people in the car with me look especially friendly. It was a very tense time.

One of the places we stopped to drop people off happened to be a very pro-Hezbollah neighborhood. We got stuck in a traffic jam on a very crowded street that was covered with posters honoring those who they described as “martyrs” who had recently died fighting in Syria.

I sat in the back seat and hoped that none of the other passengers would ask where I was from. Fortunately none did.

This was the only time riding a taxi anywhere in the Middle East where I was content to not have the opportunity to speak Arabic.

(13) Find a Language Partner:

Put up a sign on a bulletin board at any local university. You will find quality people who want to practice with you. You speak one hour in Arabic, one hour in English. The only downside is that you are speaking in English some, but the upside is you get the built-in structure. So you can plan.

This is also a tactic you can do anywhere in the Middle East. If you are working in say, Saudi Arabia or Qatar, you can always find quality conversationalists that will want to swap hours so they can get better at English. It’s also something that works very well if you are back home at your local university after a period of study onsite in the Middle East.

(14) Pay Someone to Practice Speaking to You:

My friend Chris sold me on the merits of this approach. It was a good arrangement. I met one of his friends on the AUC campus and we just spoke in Arabic on specific topics I chose – in this case it was movies (more on that in point 16). I had watched a really good Egyptian movie and marked about 20 scenes where I wasn’t 100% sure of the meaning. We sat there and talked about it.

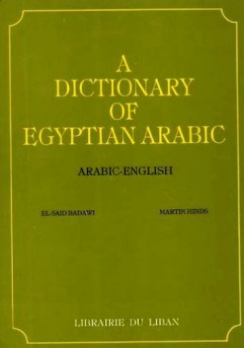

(15) Find a copy this book:

It is an extremely valuable resource for those looking to develop their speaking skills. Read why HERE. A distinguished reader and Arabic professor at the American University of Beirut added an extremely informative comment with comprehensive information on other dictionaries for spoken Arabic.

Section III: Media Strategies

Compared to 15 or 20 years ago in the pre-internet age, there are virtually unlimited online resources that creative students can take advantage of to become very high level Arabic speakers.

# 16 – Watch Movies for Situational Expertise:

This is a proven way to get an elite grasp of spoken.

What you can do is pick a movie, and watch it several times (as in 4 to 6). The first time you watch, there will be big gaps in your understanding, but that’s ok. Watch it a second, third, fourth time, and then in combination with some of the tactics from Section 2, you can get clarification (13 & 14 specifically).

It’s easy to buy good movies in Cairo, for at most $2 or $3. There is an entire block of movie stores, just a 2 minute walk from Talaat Harb square, located here:

There are at least 5 video stores that sell Arabic movies in the greater Hamra vicinity in Beirut (there is one on Bliss St next to AUB). The same will occur in any other Arab city, such as Amman or various cities in Saudi Arabia.

I recommend picking a few movies — say 4 or 5 – and becoming “experts” on them, rather than watching a large amount which you only know in lesser depth. It’s a time management issue.

Here are some good movies in no particular order that I recommend off the top of my head with interesting dialogues. I will probably dig deeper and make a list of good movies the Arabic student should watch:

(1) Tito

(4) Harb Italia

# 17 Aim for “High” Ammaya:

If your goal is to learn Arabic for practical purposes (let’s say for careers in diplomacy, business, law, journalism etc), you want to strive to learn “High Ammaya.”

One problem with some of the tactics listed in section one is that you are more likely to learn “Shaabi” or what we might call Common Arabic (especially 8 and 9 and to some extent 10). If you’re not careful you can come away speaking Arabic like a street vendor. There is nothing wrong with that per se, if that’s the goal. For example, maybe you want to write a book on Shaabi Arabic and I know people who do.

However, if you are going to be using Arabic for day-to-day usage in careers in fields such as law or consulting or diplomacy etc you want to be able to command authority and respect with your speaking. If you talk “ultra-street” to people from the “street” – they will be less deferential to you than if you speak with a more refined dialogue.

Whereas if you talk “ultra-street” in diplomatic or business functions, it would be the equivalent of talking like Ali G in this interview with Donald Trump. In other words, your Arabic will sound strange and out of place:

For that reason, you should aim for High Amaya- MSA hybrid, but with the ability to mix in some “Street,” when necessary, for effect.

One media show that is great for this is the 1980s Egyptian TV series Rafat Al-Hagen. It is probably one of the most-watched TV shows of all time in Egypt. It is as “High” colloquial as anything I’ve seen in Arabic media. Even better, all of the episodes can now be found on Youtube:

#18. Media Transcripts:

Read transcripts out-loud to yourself

Al-Jazeera until recently provided transcripts of every single talk show it produced. It is impossible to overstate how useful these are as a resource for Arabic students.

Aim for topics you are interested in and there is something for everyone. Just read the transcript aloud for 30 minutes. It will do wonders for internalizing sentence structures, phrases, debating tactics and styles etc. You will also work the tongue and throat muscles and get into the physical Zone I covered in strategy 3.

There are so many variations for what the student can do with this tactic that could easily be the source of another long post which I may write.

#19. Accent The Transcripts:

To show students the takeaways they can get from this tactic, I spent five minutes watching an excellent 2008 Al-Itijah Al-Muakis episode that featured a heated debate between a British diplomat speaking in excellent Arabic and a Tunisian Anglophobe.

I then marked it exactly as I would have when I was studying Arabic as a formal student. As you can see, no shortage of takeaways:

Key point: there is no such thing as “the only correct version” of Arabic.

The British diplomat in the above debate used Fusha and Amaya in the same paragraph multiple times. Did anybody stop to tell him that was wrong?

Hence, what I consider a “Golden” rule:

If you heard something said a certain way on Al-Jazeera, it is correct.

This is also a great tactic for people looking to keep up their skills while they may be back in their home country for a period of time, and not in a position to speak alot in person with Arabic speakers.

#20. Record Yourself Reading the transcripts and then listen to yourself:

This is an extremely useful tactic. Buy a recorder (most laptops today should have one built-in) and read a transcript out loud. Then listen to yourself. Hearing yourself speak activates a different part of your brain that affects retention.

Using Tactics 18 and 19 you have the accents marked, so you know how everything is supposed to sound. If your accent sounds “off” keep reading it until you sound the way people talk on the original recording. This is also a good way to get into the “physical” mindsets I discuss in Point 3.

Conclusion:

Becoming a high-level Arabic speaker is not easy. Nothing in life that is worth doing ever is. But it isn’t impossible. If you follow some of all of these 20 strategies, tailored to your specific situation, you certainly can become impressively fluent.