A guide I put together for current and future students of Arabic.

Section 1: My philosophical Approach To Learning and Teaching Spoken Arabic

(1) A Hybrid of MSA and Colloquial(s) Can be your Goal:

There is a strong tendency for Arabic as a 2nd language programs to compartmentalize their teaching of spoken versus written. A typical school will offer one course in Colloquial Arabic and then several on formal Modern Standard Arabic.

Practically speaking, they are often treated as two separate and distinct languages. Many a student who has slipped into MSA in Amaya class and Vice Versa has heard this from their teacher:

“Sorry, you can’t say that. Wrong class.”

There are of course some good reasons why it’s taught that way. But I started to question that conventional approach in the years after I finished being a formal student and started traveling around the Middle East for work.

Like many students, I had first studied Arabic in Egypt where I internalized Egyptian. This led to a job in the environmental sector in Saudi Arabia. In the Kingdom, the natural Arabic instinct coming out of my mouth was, logically, Egyptian.

I tried to adjust as much as possible and use Saudi phrases. This was important diplomatically. Yes, it is true, while a foreigner who speaks any Arabic will get some “points” initially, after a certain period of time it would sound odd to keep using Egyptian phrases.

Then the whole process repeated itself. I co-founded a company that – to make a long story short – unexpectedly led to me spending a fair amount of time in Lebanon. Same thing. In Beirut the instinctive Arabic words coming out of my mouth were Saudi.

I was torn. Wasn’t this a cycle that could go on forever? Each time I went to a different country? Hadn’t I finished being an Arabic student? Or would I have to relearn new colloquials over and over?

After much thought, I concluded that it may not be necessary to keep acclimating to each regional version of Arabic. I also began to rethink the practical utility of the dominant academic approach to the Ammaya/Fusha divide.

My thinking was this as a non-native student of Arabic:

I am neither a local, nor am I trying to become a professional linguist. My goal was not to be an “expert” on any specific dialect. It was to communicate at a high-level, in a broad variety of work-related practical situations. Equally important, my goal was to do this anywhere in the Middle East while not knowing in advance where that location might be.

For all of those reasons, while some teachers will hate me for saying this, I tell today’s generation of Arabic students that it is perfectly fine to aim for a spoken hybrid of, say, 60% MSA and 40% one or more dialects. More on this in Strategy 17.

What I think is the Important question:

Does whatever combination of Amaya and MSA you speak, get you the results you want?

If it does, it is no less correct than other views out there. Much more on this later in the post.

(2) Academic Teaching of Spoken: Structure Matters

In my humble opinion, formal academic instruction is less critical for learning spoken Arabic as with Written. Still, good teachers, especially at the early stages, makes a huge difference.

On that note, I strongly recommend International Language Institute in Cairo where I studied several times from 2006 to 2008. There were two unique elements to their approach. First, ILI put together organized and structured books on spoken Arabic. Scenarios with different themes such as:

- dealing with problems at work (10 or so different scenarios)

- planning for a trip to the beach (same variety of contingencies etc)

- how to explain when you are angry with someone (10 scenarios etc)

- various ways to return an item to a store etc etc

The lessons were situational and practical. I walked out of class every day with a clearer, structured, grasp of Ammaya than I walked in with. I felt confident I could turn around and successfully teach that lesson to someone at a level just behind me.

Which is precisely my benchmark for what makes great teaching or training: students or employees who have just learned a lesson should ideally be able to teach it effectively to the next class. My philosophy is that all teachers as a general ideal, should be aiming to potentially teach themselves out of a job, as odd as that might sound.

The second “value added” I saw in the ILI approach was that they put the Arabic spoken in print, in Arabic letters. This compares to other Arabic as a 2nd language programs which often transliterate spoken. I am convinced that in teaching colloquial Arabic, the words should be written out.

Why? In practice, the middle column means less to the foreign Arabic student who is studying both written and spoken (although it is true that there is an argument for transliteration for students only aiming at spoken). If students are already studying written, writing spoken Amaya out in Arabic letters creates an economies of scale studying effect:

Finally, one of my sources gives me the following tip on a new textbook with a different approach to teaching Ammaya:

“One approach they should be aware of though is the “Living Arabic” textbook” published by Munther Younes at Cornell. This approach is starts by teaching ‘Ammiyya and then uses that to approach formal Arabic. I’ve heard good things about it. If Cornell or any other university is teaching intensive summer programs around that textbook, that would be a good choice for beginning/lower intermediate students.”

(3) Treat Arabic speaking as a “physical” activity – get in “The Zone”

Too many students spend a year or two in the Arab world and leave without reaching a high-level of spoken Arabic. Why? My theory is that not enough emphasis is put on how learning how to read and write are separate activities.

Speaking is closer to the skills required for a sport, like playing basketball or acting in a play.

Here is what I mean:

First, with speaking the student has to exercise physical parts of their body. They must use various muscles, such as their tongue and throat, not just their brain, which is the only part they are using to read and write.

Most importantly, there is the “performance” aspect.

Let me give you an example. A few years ago I was visiting an international court in Europe. I noticed a woman doing stretches and jumping jacks outside the building. She also seemed to be talking to herself.

Intrigued, I struck up a conversation. I learned that she was an interpreter. This was her routine to get in the right physical and mental mindset for the “perform on the spot” activity of interpretation.

Students aiming to advance their spoken skills should think about getting in the “speaking zone” – similar to what you do if you were preparing to play a sport, like basketball.

Speaking is a physical and social activity. The problem for many study abroad students is that they spend huge amounts of time in the library in highly-introverted solitary settings, focusing on studying written.

They aren’t in “The Physical Zone:”

Could a basketball coach put a player into a game with no warmup and expect them to succeed? Of course not. The same thing is true with languages. Switching from the Written-Mental to the Physical-Spoken mindset can be difficult. It certainly doesn’t happen automatically.

You have to get in “The Zone” to be effective.

Some tips I recommend:

- Have a physical “warmup” – read aloud an Arabic newspaper for 15-30 minutes before you know you will be speaking Arabic. Much more on this later in the post (strategies 18 to 20).

- Get in a social mood, whatever that takes. One thing you can do is watch shows like Seinfeld.

- Try and of the ideas in Strategy 6

(4) The 250 Hour Golden Rule:

When I look back at everyone I know over the past ten years who became high-level Arabic speakers, compared with those who didn’t, every case is explained by this core Golden Rule:

In order to become very good at speaking, the Arabic student must spend 250 hours speaking Arabic in non-classroom situations.

If the student finds a way to generate 250 speaking hours, they will reach a very high level. If not, they don’t. It goes without saying, of course, that 500 hours is better than 250, and 750 is better than 500 and so on.

If you are studying abroad for even one semester, there is no reason you can’t reach 250 hours.

Section 2 will focus on strategies for getting those quality speaking hours.

First though, points 5 and 6 offer my thoughts on the nature of those 250 hours of conversations.

(5) Cherish Good Conversationalists

Cateris Paribus – one hour spent with an engaging conversationalist – someone with an interest in lots of topics who reads lots of books – will be more beneficial to your skills development than several hours with the hardest-core and most one-dimensional “Meathead.”

Therefore, in general, the Arabic student should seek out and spend time talking with great and engaging conversationalists.

(6) If you don’t sometimes feel nervous, you aren’t working hard enough

Still, this point might sound like I am contradicting the previous point. There is a down-side in spending too much time speaking with the Good conversationalists. In practice they are likely to be your Arabic professors or their friends, for example.

Anyone can sit down, at a time of their choosing, with someone whom they are familiar and comfortable with, who knows your speaking patterns and wants to help you, and “perform” Arabic (or any language for that matter).

Whereas the key to really getting good at spoken is making sure a huge portion of your 250 hours take place outside of your comfort zone. You want:

- To be in situations where you nervous

- To be in situations where you are “rattled,” if not embarrassed

That’s perfectly fine. It’s the only way you will get really good.

In fact, my proudest moments as an Arabic student came after I was a formal student. And they occurred precisely because during my days as a student I put myself in hundreds of these types of “stressful” situations.

One time we were in the Eastern Province, deep in the Saudi country side. Two tires blew out on one of the vehicles. There was some other potentially serious technical problem.

As the logistics person for the trip, I drove with one of my team members to find the local mechanic.

It was a stressful situation. We were near the border in the complete middle of nowhere. There had recently been all kinds of warnings about escalated Al-Qaeda threats in this specific area. The Arabic words just came out. Adrenaline took over. I was in “the Zone.” I didn’t even think.

Another time I was driving home from work in Jeddah when an Iranian diplomat (red), upset at my apparent “slow” speed, sideswiped my car trying to get around me (blue).

Here is why this matters Arabic-speaking wise:

While the Iranian guy was 100% at fault, his car had significant cosmetic damage. Mine had basically none. This meant I was potentially vulnerable if it came down to a He-Said, She-Said situation.

Why? Theoretically, the same US driving laws are on the books in the Kingdom. However, the only thing that means for certain is that there is a piece of paper someone that says “these are the driving laws.”

In practice, there isn’t usually a standard system for investigating traffic accidents and apportioning blame in some kind of objective way (at least I never saw one). Therefore, the person who “didn’t cause the accident” is the one who is:

- Better at yelling and/or firmly asserting their case more convincingly to the traffic cop

- Is more liked by the traffic cop for whatever reason

- Some other unknown factor that is impossible to figure out

Again, adrenaline took over.

I was assertive and calmly made my case in Arabic to the Saudi traffic cop. I clearly described everything that happened. He decisively took my side and told me to go home, he’d take care of it from there. My teachers would have been proud.

The Arabic words just came out. I didn’t think. The whole exchange “just happened.”

I reacted and spoke effectively, due to my Arabic learning strategies from my time in Cairo. I had intentionally gone out of my comfort zone enough times while studying, that in practical “Real World” situations I just acted and felt reasonably comfortable doing it.

How can you simulate “outside of your comfort zone” situations?

Here are some ideas:

(1) Take 5 minutes to research terms related to vacuums or some other device that you need to buy. Then Go into a department store, and ask for the pros and cons of the vacuums they have on stock. Only in Arabic. Preferably if there is a line behind you.

(2) Intentionally “get lost” in a neighborhood in the Arabic city you are studying. Then ask for directions in Arabic back to the spot you know and find your way back home. If anyone tries to help you in English, say you are from a country where no one would know the language: Mongolia.

(3) Phone calling — so much of communication is conveyed by body language, seeing each other and that is often a crutch for Arabic students: just call a restaurant to order; call the department store to ask about stuff etc.

(4) Join a gym where you are out of your comfort zone- see point 11

(5) Each person is different — just find any situation where you know you will be more uncomfortable in Arabic – and do it 50x, over and over

Section II: Lifestyle Strategies To Generate 250 Hours

In this section I will reflect on all of the various tactics I recall my fellow students using to get really good at spoken Arabic.

(7) Minimize Contact with Anyone Who Wants To Speak English:

Extremely important. Anywhere you study in the Middle East, you’ll find locals who want to practice speaking English. There are also going to be fun expat communities with interesting people to hang out with. There are no shortage of opportunities to revert to your comfort zone and speak English.

I don’t recommend you be an Immersion Extremist and speak Arabic 24-7 unless you really want to. You don’t need to in order to get good at spoken.

However, you must be disciplined about limiting your English. Consider a business-hours time mindset, where you get eight hours of Arabic in, maybe during the day, and then are more relaxed at night.

Paths to Assimilation :

In the most perfectly fun and interesting world, the foreign Arabic student could find some kind of “Friends”-type living arrangement during their time in the Middle East. In that arrangement they live only with hip locals who conveniently speak not a word of English.

Perhaps such situations exist for students studying Chinese in China, or Spanish in Spain or French in France etc.

Unfortunately for the Arabic student they don’t exist in the Middle East. In conservative Arab cultures (Lebanon included – and all of sects), 99% of people live with their parents until marriage. And the maybe 1% that would live alone are likely to speak very good English.

This means that the foreign Arabic student has to be more creative in finding ways to get the full immersion aspect needed to generate 250 hours. Here are some ideas that I observed or tried during my formal days as an Arabic student:

(8) Live in a Slum (extreme assimilation):

My friend “Chris” took this approach. It was not for me. This was hard-core assimilation, dirt floors, the complete lack of material comfort etc. Although at $20/month, he was saving money on rent.

The results did speak for themselves. Chris’ Egyptian colloquial skills were better than anyone else I knew. However, in today’s political and security climate in most Arab countries, I would generally recommend against this approach without conducting serious research before hand.

(9) Ride the Minibus every day (slightly less extreme assimilation):

My friend “Steve” rode the mini-bus (basically a van that runs along a fixed route) as his primary form of transportation, for the purpose of speaking Arabic.

This is a good idea strictly from the learning-Arabic angle. Theoretically, you are sitting next to someone for a long period of time in a way that naturally facilitates conversation that wouldn’t occur on say, a metro. Again, the results spoke for themselves: Steve’s spoken Arabic skills were very very high.

More importantly – is this is a good idea from a safety perspective?

Yes, on one hand, the student may find themselves sitting next to an Egyptian, who never in a million years would have guessed they’d encounter a fluent American Arabic speaker sitting next to them on a minibus, and have some great conversations.

On the other hand, if you do it enough times these days, the Arabic student is statistically likely to eventually find themselves sitting next to someone as eager to beat up such an American, rather than help them practice their language. Therefore, in today’s Egypt I would say this specific tactic is generally not a good idea. I wouldn’t do it myself.

Middle Ground Assimilation

(10) Live in a Non-Elite Area:

Where the Arabic student chooses to live will effect their ability to generate quality speaking hours. Live in a “nicer” area, your lifestyle will be more comfortable. Perhaps more “fun” depending upon how you define fun.

Whereas if you live in the more “Shaabi” or common areas, it may not be as enjoyable. The tradeoff, however, is you will generate vastly more speaking encounters. You will get to 250 speaking hours faster and more efficiently.

Why? In more upscale neighborhoods like Zamelek or Maadi in Cairo, or Hamra in Beirut, you are just another foreigner. Whereas if you live in places like Sayeda Zeinab, the foreigner is something of a novelty. People will want to talk to you.

Each local city will differ. I do still with caution recommend this strategy in 2016, but only after students do their local research. Talk to your teachers, ask other students who have been at your school for longer. Ask them what they think about which neighborhoods would be good for this strategy.

(11) Join a Gym:

But not just any gym. During one stretch in Cairo I joined two gyms. The first, “Fitness Academy” was solely for exercise. It was your standard US-style gym. During my entire 6 month membership at $90/month, I maybe spoke 15 minutes of Arabic. I was just another foreigner at Fitness Academy.

Gym # 2 was called “Boondock” ($5/month) and was for speaking Arabic. It was located in one of the more blue-collar neighborhoods near Tahrir Square.

Some of the guys there were on steroids. Many of the members were as ripped as Arnold or Rocky if not more. Although it’s also true that as the gym had no cardio equipment I suspect if asked to run 1x around the block, several would pass out.

There was one primary reason for the Arabic student to join. To get the kinds of hours I mention in point 7, especially the unconventional hours discussed in point 6.

(12) Make the Most of Riding in Taxis:

In at least 500 taxi rides in the Middle East, I have easily had 50 quality hours of conversation, probably closer to 100, maybe even more.

Ways you can develop your spoken Arabic skills in a Taxi:

- If you’re going a specific route every day, passing some specific landmark, that’s a natural thing to talk about; ask them a question about it etc etc. Then the next day, ask the same question to a different driver….

- Some issue that every driver will have an opinion on. Talk about it. Almost all will have an opinion on say, soccer teams etc. See point 16 for another suggestion.

That being said, the safety factor is more important in a post-2011 environment. You have to be more careful nowadays.One example is worth mentioning to illustrate new post-Arab Spring realities. (I address the safety issue in great depth in this post)

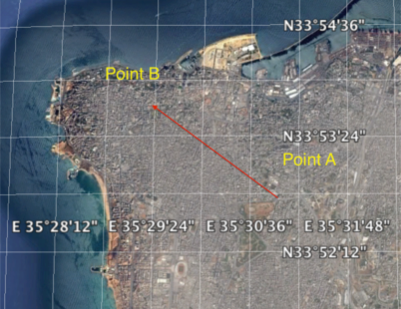

It took place during the summer of 2013 in Lebanon. I had a meeting in the Central area of East Beirut (Point A) while staying at a hotel in Hamra (point B). This is what I wanted to happen afterwards – quickly find a Taxi and do this:

Unfortunately that didn’t happen. For at least 20 minutes afterwards, even after moving streets multiple times to get a better spot, I was unable to find any taxi.

Not being able to find a taxi isn’t usually the end of the world.

However, this was a very tense time politically in Lebanon.

President Obama seemed to be about to order an attack on the Syrian government. Whatever you think about whether that was a smart idea or not, it meant that there would likely be retaliation by Assad’s allies in Lebanon against US interests inside Lebanon if Syria was attacked.

I don’t look Lebanese.

Eventually, a “Service” (basically a group taxi) stopped. Sure, he’d go to Hamra as soon as we dropped the other passengers off.

Given the tense security climate – this was something I didn’t really want to do. Though with no other options I crossed my fingers and got in.

These “other neighborhoods” weren’t exactly on the way to Hamra. Nor did the people in the car with me look especially friendly. It was a very tense time.

One of the places we stopped to drop people off happened to be a very pro-Hezbollah neighborhood. We got stuck in a traffic jam on a very crowded street that was covered with posters honoring those who they described as “martyrs” who had recently died fighting in Syria.

I sat in the back seat and hoped that none of the other passengers would ask where I was from. Fortunately none did.

This was the only time riding a taxi anywhere in the Middle East where I was content to not have the opportunity to speak Arabic.

(13) Find a Language Partner:

Put up a sign on a bulletin board at any local university. You will find quality people who want to practice with you. You speak one hour in Arabic, one hour in English. The only downside is that you are speaking in English some, but the upside is you get the built-in structure. So you can plan.

This is also a tactic you can do anywhere in the Middle East. If you are working in say, Saudi Arabia or Qatar, you can always find quality conversationalists that will want to swap hours so they can get better at English. It’s also something that works very well if you are back home at your local university after a period of study onsite in the Middle East.

(14) Pay Someone to Practice Speaking to You:

My friend Chris sold me on the merits of this approach. It was a good arrangement. I met one of his friends on the AUC campus and we just spoke in Arabic on specific topics I chose – in this case it was movies (more on that in point 16). I had watched a really good Egyptian movie and marked about 20 scenes where I wasn’t 100% sure of the meaning. We sat there and talked about it.

(15) Find a copy this book:

It is an extremely valuable resource for those looking to develop their speaking skills. Read why HERE. A distinguished reader and Arabic professor at the American University of Beirut added an extremely informative comment with comprehensive information on other dictionaries for spoken Arabic.

Section III: Media Strategies

Compared to 15 or 20 years ago in the pre-internet age, there are virtually unlimited online resources that creative students can take advantage of to become very high level Arabic speakers.

# 16 – Watch Movies for Situational Expertise:

This is a proven way to get an elite grasp of spoken.

What you can do is pick a movie, and watch it several times (as in 4 to 6). The first time you watch, there will be big gaps in your understanding, but that’s ok. Watch it a second, third, fourth time, and then in combination with some of the tactics from Section 2, you can get clarification (13 & 14 specifically).

It’s easy to buy good movies in Cairo, for at most $2 or $3. There is an entire block of movie stores, just a 2 minute walk from Talaat Harb square, located here:

There are at least 5 video stores that sell Arabic movies in the greater Hamra vicinity in Beirut (there is one on Bliss St next to AUB). The same will occur in any other Arab city, such as Amman or various cities in Saudi Arabia.

I recommend picking a few movies — say 4 or 5 – and becoming “experts” on them, rather than watching a large amount which you only know in lesser depth. It’s a time management issue.

Here are some good movies in no particular order that I recommend off the top of my head with interesting dialogues. I will probably dig deeper and make a list of good movies the Arabic student should watch:

(1) Tito

(4) Harb Italia

# 17 Aim for “High” Ammaya:

If your goal is to learn Arabic for practical purposes (let’s say for careers in diplomacy, business, law, journalism etc), you want to strive to learn “High Ammaya.”

One problem with some of the tactics listed in section one is that you are more likely to learn “Shaabi” or what we might call Common Arabic (especially 8 and 9 and to some extent 10). If you’re not careful you can come away speaking Arabic like a street vendor. There is nothing wrong with that per se, if that’s the goal. For example, maybe you want to write a book on Shaabi Arabic and I know people who do.

However, if you are going to be using Arabic for day-to-day usage in careers in fields such as law or consulting or diplomacy etc you want to be able to command authority and respect with your speaking. If you talk “ultra-street” to people from the “street” – they will be less deferential to you than if you speak with a more refined dialogue.

Whereas if you talk “ultra-street” in diplomatic or business functions, it would be the equivalent of talking like Ali G in this interview with Donald Trump. In other words, your Arabic will sound strange and out of place:

For that reason, you should aim for High Amaya- MSA hybrid, but with the ability to mix in some “Street,” when necessary, for effect.

One media show that is great for this is the 1980s Egyptian TV series Rafat Al-Hagen. It is probably one of the most-watched TV shows of all time in Egypt. It is as “High” colloquial as anything I’ve seen in Arabic media. Even better, all of the episodes can now be found on Youtube:

#18. Media Transcripts:

Read transcripts out-loud to yourself

Al-Jazeera until recently provided transcripts of every single talk show it produced. It is impossible to overstate how useful these are as a resource for Arabic students.

Aim for topics you are interested in and there is something for everyone. Just read the transcript aloud for 30 minutes. It will do wonders for internalizing sentence structures, phrases, debating tactics and styles etc. You will also work the tongue and throat muscles and get into the physical Zone I covered in strategy 3.

There are so many variations for what the student can do with this tactic that could easily be the source of another long post which I may write.

#19. Accent The Transcripts:

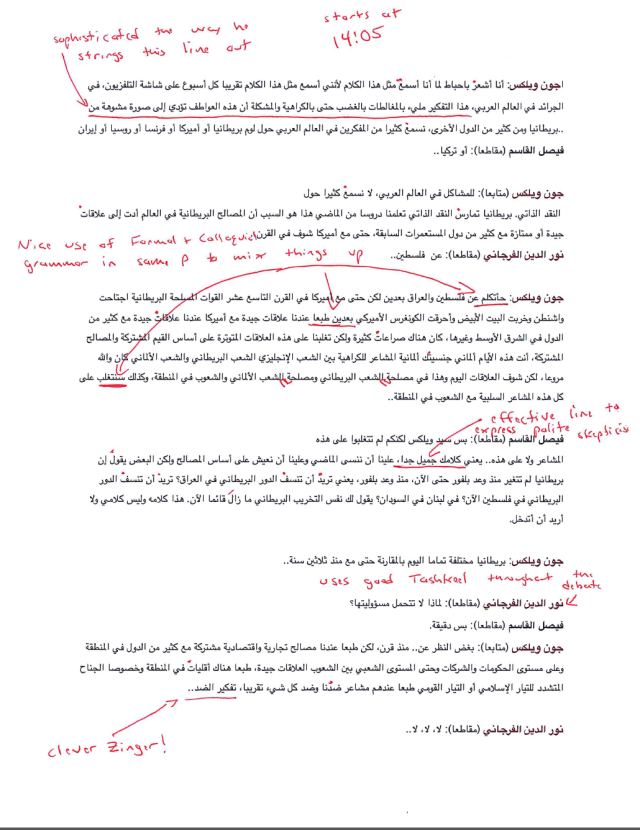

To show students the takeaways they can get from this tactic, I spent five minutes watching an excellent 2008 Al-Itijah Al-Muakis episode that featured a heated debate between a British diplomat speaking in excellent Arabic and a Tunisian Anglophobe.

I then marked it exactly as I would have when I was studying Arabic as a formal student. As you can see, no shortage of takeaways:

Key point: there is no such thing as “the only correct version” of Arabic.

The British diplomat in the above debate used Fusha and Amaya in the same paragraph multiple times. Did anybody stop to tell him that was wrong?

Hence, what I consider a “Golden” rule:

If you heard something said a certain way on Al-Jazeera, it is correct.

This is also a great tactic for people looking to keep up their skills while they may be back in their home country for a period of time, and not in a position to speak alot in person with Arabic speakers.

#20. Record Yourself Reading the transcripts and then listen to yourself:

This is an extremely useful tactic. Buy a recorder (most laptops today should have one built-in) and read a transcript out loud. Then listen to yourself. Hearing yourself speak activates a different part of your brain that affects retention.

Using Tactics 18 and 19 you have the accents marked, so you know how everything is supposed to sound. If your accent sounds “off” keep reading it until you sound the way people talk on the original recording. This is also a good way to get into the “physical” mindsets I discuss in Point 3.

Conclusion:

Becoming a high-level Arabic speaker is not easy. Nothing in life that is worth doing ever is. But it isn’t impossible. If you follow some of all of these 20 strategies, tailored to your specific situation, you certainly can become impressively fluent.

I agree about the need to stop compartmentalising fusha & colloquial and find a point somewhere in the high amiya range as a default for most interactions. The prevailing puritanical division is not based in modern reality and is unhelpful.

LikeLike

Great comment. This is a very important point. I like the emphasis on the word “modern reality.”

It’s really been maybe 20 or 30 years, at most, where there have been large-scale numbers of people traveling to the Middle East to study Arabic.

The idea that there ever was one “correct” Arabic that modern 20th or 21st century students who are not studying Arabic for religious reasons, should aim for doesn’t seem based on any kind of solid, clear foundation of a “black and white” right or wrong.

MSA as taught in practice in most universities, is definitely a subjective academic construct. It’s probably a necessary construct, you have to some kind of construct.

But given the relative “newness” of globalization, it’s also true that what is taught needs to evolve. And your wording I think is very correct:

“a point somewhere in the high amiya range as a default for most interactions.”

It would be very interesting to know exactly what kind of mix someone like Lawrence of Arabia was speaking, or any of the very few British Arabic linguists during the First or Second World Wars would have been speaking. I am fairly certain it was a default in the high Amaya range. But I would be interested to know more.

LikeLike

https://islamicarabicacademy.wordpress.com/

LikeLike

Pingback: Some Really Helpful Resources for Students of the Arabic Language – The Thinking Muslim

The spoken Arabic post is highly interesting. I need to think about it a bit more. I certainly agree that compartmentalisation is too strong currently and a product of dinosaur thinking. BUT … I also know that Arab colleagues/friends (particularly diplomats or government figures) are horrified when spoken to in overly colloquial Arabic by westerners who focus only on getting the point across rather than picking their register to suit their audience. The latter clearly isn’t what you mean at all, but I worry that too many institutions sacrifice attention to detail to meet the need for quick solutions and fast training. This creates a “one size fits all” Arabic, which is better than the old obsession with diglossia and can be sufficient for many needs. However, it lacks the nuance and appreciation of linguistic register needed to undertake some jobs (especially negotiations) effectively. Courses need to ensure that their beneficiaries – both students and employers – understand what they’re getting and what it’s good for.

LikeLike

Elisabeth,

Thanks for this comment and bringing up this point.

You’re right, I am not advocating the “one sized fits all” Arabic that you have pointed out that some institutions seem to be aiming for, although I could see how it might be perceived that way. Because of your comment I tried to make clearer in point 1 to look at the references to High Ammaya in point 18. I think that is a good conceptual middle ground between some of these approaches, especially for those aiming for region-wide utility.

And this is a critical point:

“horrified when spoken to in overly colloquial Arabic by westerners who focus only on getting the point across rather than picking their register to suit their audience.”

I think there is probably a unique American mentality that downplays the importance of talking to the level of the audience. “Why should we talk to a Bowab any differently than the way we talk to a high-level person?” “That’s just not right.” I can’t provide hard scientific evidence of this, but I do see people I know accepting the idea that “speaking hard Amaya is good enough.” Not necessarily by teachers of the language, but by students.

Whereas by contrast I think there is a stronger European tendency (especially continental, French) to accept the idea of the spoken-hierarchal emphasis, ie the idea that you would really take the time to invest in speaking to their level and shifting your language level to conform to the status of whom you are talking to.

That difference is entirely consistent with certain mentalities in the US, where we have more of an “everybody gets a medal” for participation mentality, which makes many people relucant to overtly even say you should aim to speak to a Bowab differently than an ambassador. I think this has something to do with what you are getting at.

Nathan

LikeLike

Greetings… aTaib al-Tahaiya wa b3dhaa…

Ref that insightful and important point “horrified when spoken to in overly colloquial Arabic by westerners who focus only on getting the point across rather than picking their register to suit their audience.”

That is actually an understatement when one is involved in interpreting or interacting during protocol-loaded situations. In those cases, go with MSA, but insure that the foreign speaker also adds the suitable honorifics and protocol utterances.

A learner of Arabic who likely will be involved in protocol-sensitive dealings with high-status (and usually status-sensitive / touchy) Arab rapporteurs — i.e. Saudi Arabian royals ministerial officials, senior officers and local / tribal dignitaries — absolutely must, and BEFORE those encounters, ask reliable and knowledgeable local contacts for the appropriate utterances, protocol amenities, and forms of address appropriate to the rank and status/position of the Arab conversant.

In that regard, I can recount some cringe-worthy and ultimately-negative situations (wherein the bilateral talks either were suspended or noticeably turned frozen) when an American participant with a “fair-to-middlin'” formal background in Arabic slid into Egyptian Amaiya during interactions with an educated and urbane visitor from Saudi Arabia or other GCC country (Yemenis are another, and opposite, matter, as they frequently express surprise / astonishment and affection for any foreigner who uses colloquial Yemeni Arabic with them, such as during medical appointments at specialty clinics here in the US).

FYI, the equivalent address honorific of “sir” in Egyptian amaiya = “effendim” (historic Turkish loanword) in Saudi / Gulf Arabic Local Dialect Arabics (LDAs) = “Taal 3mrak” [ طال عمرك ] or (less frequently) “Taweel al-umr” [طويل العمر] when dealing with, and addressing, non-royal prominent persons.

Two excellent and relevant sources on “formal protocol Arabic” — both findable via online searches of used book vendors and (probably also) [no plug intended or implied] — that I have used over the years are by the late Sir Donald Hawley. They are:

[1] Courtesies in the Gulf Area

Softcover, ISBN 1900988038

Publisher: Stacey International, 1998

[2] Debrett’s Manners and Correct Form for the Middle East

Hardcover, ISBN 0905649672

Publisher: Putnam Pub Group (T), 1992

Alternatively, when the Arab counterpart switches to his local amaiya — i.e. Najdi, Hejzi or Hasawi — during a conversation with a foreigner (who has shown some awareness of that local amaiya) after the formal or substantive topics have been discussed and resolved, that code-switch sends a number of strong, implicit and positive signals to the nearby attendees and listeners about how the Arab participant has come to appreciate and trust the foreign speaker.

Agree with the author about the profound benefits of selective self-immersion during daily routines, i.e. local barber, dry cleaners, visiting different sectors of the souq district in a learner’s overseas “home town.” Those interactive social exchanges can quickly smoothen a learner’s speech in Arabic from sounding like a walking dictionary (“qaamoos maashii”) to a more-natural and more-local form.

Looking forward to reading and enjoying the other posts in this fine blog.

Khair, in shaa’ Allah.

Today is Monday, May 16, 2016.

Regards,

Stephen H. Franke

San Pedro, California

(Formerly of Egypt, Sudan, Jordan, KSA,

UAE, Bahrain, and the general Gulf area)

LikeLike

Steven is mixing apples and oranges when he compares interpreting at high-level diplomatic meetings between Gulf dignitaries and interpreting for Arabic-speaking patients at clinics in the US. The type of interpreting used in the former is usually called ‘consecutive interpreting’ while that in latter it is usually called ‘community interpreting’. Professional interpreters are trained in the oral production of fuṣḥā precisely because that is the currency in in the conference booth and in other such formal language mediation situations like diplomatic encounters. There, the use of any dialect is entirely inappropriate. And that is probably what led to the chilly receptions from the Arabic-speaking dignitaries. They expected trained interpreters. Meanwhile, in community interpreting, the situation is reversed: the use of fuṣḥā is inappropriate. In those situations, the interpreter is often dealing with people of modest education who are untrained in the active use of the formal registers – having no need for them in their daily lives – but who need to have interpreted to them vital information conveyed to them by physicians, government or aid agency personnel, or legal officials. They often find themselves in emotionally-charged, life-and-death situations such as seeking medical treatment, relief benefits, or defense against civil or criminal charges. And they need to have the relevant information conveyed to them in their native language. The use of fuṣḥā in such situations would strike the principals as excessively and inappropriately formal. Indeed, it risks the breakdown of communication. The only time fuṣḥā would be used would be in something like court interpreting in an Arabophone setting, say an accused who does not speak Arabic in a courtroom in the Arab world. Then, the interpreter would relay the principal’s communications to the Arabic-speaking officials in courtroom in fuṣḥā. Those kinds of situations are extraordinarily rare, however, and obviously require a trained interpreter. But community interpreting with Arabic speakers outside the Arab world is a daily occurrence. Community interpreters need a different sort of training, not just language, but the practice of various emotional distancing strategies and empathy building strategies. The interpreter in the conference booth or the diplomatic session doesn’t usually need that, although they are trained in conveying affect in their performances. The consecutive interpreter, on the other hand, is trained in palliating affect.

In point of fact, non-native speakers of Arabic, at least those trained at western institutions, rarely reach the level of proficiency required for interpreting into Arabic in the conference booth or at formal diplomatic meetings. That doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t try, though. And both Nathan’s and Steven’s point about attention to register is entirely apt. The notion that all you need is ammiyya so that you can go out in the street to talk with the common man or interact with friends is limiting in the extreme, and it displays a profound ignorance of the realities of Arabic usage in its native setting.

On that point, I have to demur somewhat from Nathan’s strategy of living in a slum. I did it. And as soon as I assumed my first position of responsibility in an Arabophone setting, I found that the local dialect that I had acquired and was using in my first meeting with my staff was inappropriate to the class setting in which I found myself. I didn’t even notice it while it was occurring. My assistant later told me that I was addressing the women inappropriately to my status. It as a simple thing having to do with the correct form of the honorific (madam so-and-so instead of sitt so-and-so), but it made me sound like a street urchin.

And about the use of honorifics. It is, indeed, a highly nuanced social sensitivity. Nothing can mark the Arabic learner as an outsider as quickly as the use of out of place social niceties, such as titles, or in the American sensibility and usage, their complete absence from discourse. Lamentably, these things are not taught in the usual Arabic curriculum, so the Arabic learner should, as in all things, exercise constant vigilance to the social situations occurring all round.

And, as to that, Hawley’s Courtesies in Oman, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and the Gulf is, as the subtitle says, a dictionary of colloquial phrase and usage. So it would not be of much use in a formal interpreting situation, at least not until the formalities were dispensed with.

I don’t have the Debrett’s manual (I just ordered it from Abe’s books). But I would suppose that if it is in the Debrett’s series, it probably does address a more formal register.

Long ago, I used a prototype of Rammuny’s Business Arabic, which provided a long list of the appropriate titles to use with dignitaries of all stripes. It is available through the U of Michigan Press:

https://www.press.umich.edu/8417/business_arabic_intermediate_level

LikeLike

Great article and thank you so much for sharing your wisdom and experiences. I do have a question which you may or may not be able to shine a light on. This is all geared for living over seas and becoming a high level speaker but do you have any advice to those who are not able to live in a predominately Arabic speaking area? I am aware that it would be difficult to get to such a high level while not immersing yourself completely, however, I would still love to do what I can to improve speaking while here in the states. Any tips or suggestions that you might possibly have would be greatly appreciated!

LikeLike

Kelsey,

Great point. My thoughts:

-If you are going to be studying Arabic in the Middle East, don’t spend all of your resource hours focusing on written. Learning formal Arabic is location independent — so you can learn that wherever you can find a good teacher. Whereas there is simply no way to simulate the speaking opportunities that living in a city with millions of native speakers offers. I see alot of students spending all of their time on R+W, and leaving 2 years of studying “on site” as not great speakers because of this. It depends upon your goals of course, but something to keep in mind.

-The Language Partner strategy — can be done anywhere. Any big city or university town is going to have native Arabic speakers looking to get better at English.

-Meetup.com groups – in many big cities people meet up in conversation groups. I noticed that in my current city – DC — there are several Arabic discussion meetup group.s It’s hit or miss in terms of the level of the people there, but still, its worth checking out.

-Tutor or teacher — you should be able to find a teacher that can focus on spoken anywhere too.

-The Media strategies — easily doable anywhere. Read transcripts on topics that you are interested in. You may not advance significantly in terms of “thinking off the cuff” spoken, but you will internalize speaking patterns. You can also work on accents with this tactic.

I will think about this more because it’s a good point.

Nathan

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this wonderful document.

What books did ILI use? You also wrote that you attended in 2008. What is it like now?

I also like your focus on film but your selections are all from Egyptian cinema. What about films from other Arabic speaking nations?

LikeLike

Carla,

Glad you found the post helpful. Good points.

I haven’t had studied at ILI since 2008 so I don’t know for sure. I recommend it based on the fact that they had a strong systematic approach in place.

The book – which was produced internally – wasn’t anything super fancy, but it was an organized, structured book. All of the teachers I had were good and enthusiastic, but they taught off that book.

Any school or company or sports team can have superstars and be good for a time but you never want to be dependent upon a superstar. Whereas if you have a good system the product being put forward every is consistently good.

So based only on the above, I am confident you can still get the same high-quality speaking teaching, otherwise I wouldn’t have recommended it.

Sadly, probably the numbers are down overall. Many a good Arabic teacher in Egypt has probably lost their job over the last four years due to the decline in foreign students coming to Cairo to study. On the other hand, if you see this post I wrote two weeks ago, there are some good comments from people “on the ground” in Cairo who say it isn’t particularly unsafe for foreign students.

http://betterworld2100.me/2016/04/19/how-to-safely-study-arabic-in-the-current-middle-east/

Good point about the Egyptian films. Some of this is due to the fact that probably 90% of the good Arabic films are Egyptian. I have watched many good films from other countries, but I can’t really remember the specific names because I watched them a long time ago. I will think about this more because it’s a good point.

Nathan

LikeLike

Pingback: The most valuable resource on Spoken Arabic I have seen – Better World 2100

Thanks for great advice, I wish I’d both read and followed these steps when I was a student in Cairo back in the 1990s. As I didn’t, I’m still quite embarrassed with my spoken Arabic, though my written is good – which results in some uncomfortable situations when I have to resort to English while speaking with Arab authors whose novels I translate, whereas chatting in writing in Arabic is rarely a problem.

Anyway, I have a tip with regards to point 12 about practising with taxi drivers, a smart point a fellow student made back in the days: when chatting with taxi drivers, invent new identities for yourself which imply a challenge vocabulary-wise. And he was right, as these conversations tend to resemble interviews on the passenger’s background, opinions, etc., you soon end up repeating the same information and statements. Which means that after some time, your conversations follow a fairly predictable script. By continuously reinventing your background, and possibly new points of view, you go into uncharted territory, which poses more challenges. It really works! (I just didn’t do it enough…)

LikeLike

Geir,

Thanks for your comment. Glad you found the post useful. And it’s never too late to learn spoken Arabic and some of the tips you can do anywhere, such as finding a language partner, and watching Al-Jazeera debates.

That’s a great tip re point 12. As your student figured out, say, you can only say “I’m a student” so many times, before it gets old.

Nathan

LikeLike

I am a native Arabic speaker and currently studying Chinese. I have to say that many strategies you recommend for studying Arabic would carry over to Chinese. For example, whenever I want to practice Chinese, I spend time with Chinese native speakers or with my Chinese language partners where we always agree to correct me whenever I say something that doesn’t sound right or natural. (it is really important to agree beforehand because Chinese people would try to get what you mean rather than correcting you, they have this euphemistic way of speaking).

Also, I think that getting out of your comfort zone is very important in order to improve, although you might be in the most embarrassing situations. Once, my credit card was swallowed by the ATM, I had to call the bank and explain what happened so I can get my credit card back. At that time, I wasn’t very confident in Chinese but I researched all the terms I thought I would need and related to the banking sector to illustrate the issue. It was tough but it worked!

Another way that I frequently use is when I ride a Taxi. Most of my friends here can’t speak Chinese because they are either law or business students. It’s a good opportunity for me to communicate with the driver and talk about pretty much everything on the way.

I love watching Chinese movies, I get to learn a lot of vocabulary but I’m going to give your 16th strategy a try and watch a movie several times. I think it’s much more interesting and would help me grasp a lot more of the language.

Sometimes it’s difficult to practice Chinese because Chinese people all want to practice their English with you. At first, I used to reply in English but later decided to say that I don’t understand English and that I’m from Lebanon (most of them don’t really know where it is) which is a good tactic to forget about English and speak Chinese. They are also usually very happy to hear you speak their language.

I still say that the most challenging part in Chinese is the speaking, especially because it’s a tonal language. This is why I sometimes record myself reading texts and ask my language partner to correct my pronunciation and tones.

I really enjoyed reading your posts! I’ve got a month and a half left in China and I’m going to adopt some of the strategies you mentioned and let you know about it!

LikeLike

Melissa,

Thanks for your comment. I am very glad to hear that many of these strategies apply to Chinese as well.

That’s interesting that you are finding many Chinese will be unlikely to correct a foreigner there if they make mistakes, out of politeness because I found the same thing when I was studying Arabic. That’s what is so valuable about a good language partner as you have discovered – each person can correct each other automatically.

The recording of yourself listening is a golden tactic in any language. I think people think it is weird, but to hear yourself talk on tape, is so effective in improving accent. People wouldn’t hear how they sound otherwise.

Watching movies multiple times make a huge difference. Each time you watch the movie your comprehension should improve by 20%.

It sounds like you are well on your way to developing very high level Chinese skills. As a native Arabic- English- Chinese linguist, these are going to be very marketable language skills.

Nathan

LikeLike

Greetings to all in this thread.

Dwilmsen rightly calls me out for my — inadvertently — conflating formal (MSA-centric) consecutive interpreting and community (amiya-centric) interpreting. My original note did not distinguish and contextualize those different, if not contrasting, registers. Sawwadtu wajhii.

Dwilsem also provides a helpful and considerable insight about acquiring an ultimate ability in “street-level amiya” in one setting and later discovering in an academic setting that that register was inappropriate. A parallel example from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Yemeni expatriates (almost all originated from Hadramaut and its Wadi al-Mukalla area) effectively monopolize, or heavily influence, the local trade in cell phones and subscriptions to any of the available cell phone services; ditto situation exists for most shops dealing in gold, silver jewelry, perfumes and fragrances. Those shops are concentrated in the business district radiating around the historic al-Mismak fortress in the “old downtown” section of Riyadh.

One behalf of my employer, a US contractor based in Riyadh, I frequently would patronize three of those Yemeni-run cell phone stores to buy phones and service subscriptions for our newly-arrived employees. Over time and extensive “dardasha”, the Yemeni shopkeepers accepted and absorbed (can’t think of a more-elegant descriptor) me in their social network and family circles when I had time off. During a series of visits, they were pleased to describe and proudly contrast the features of their transplanted and still-vibrant Hadrami dialect with those of the prevalent Najdi dialect.

Little did I realize how insidiously that Hadrami dialect had crept into my social and professional Arabic until one day, when I was discussing a training topic with my Saudi (Najdi origin) military counterpart. We had been working together almost daily for about seven months by then, and he had gladly become my diligent and helpful language partner. That day, after a few minutes of discussion, he began to look askance at me, and then he suddenly laughed and asked smilingly, to the effect of “What is this? You’re starting to speak like a Hadrami; are you ‘going Yemeni’ on us?”

Side observation: A subject well worthy of a dissertation is the phenomenon of dialect-leveling of what is emerging in Saudi Arabia (and to a lesser and different extent, in UAE) as “Government Official Arabic” which, as informally called by its users as “al-lughat al-waSeeta”, reflects the (ahem) “Najdification” of the Arabic spoken among staffs of most of the governmental ministries in Riyadh.

—————–

Dwilmsen is also “spot on” in his recommendation of Rajhi Rammuny’s two-volume set on “Business Arabic,” which, in its intermediate-level book, provides a long list of the appropriate titles to use with dignitaries of all stripes. That set is comparatively head and shoulders above the bunch of other recent materials on Arabic for business, management, HR, and similar professional or technical fields.

Khair, in shaa’ Allah.

Regards,

Stephen H. Franke

LikeLike

ما كان قصدي أن أسود وجهك يا صديقي العزيز !!

I always insist to students and inquirers upon the utility of learning both a dialect and fuṣḥā in order for them to become fully functional in Arabic. And the distinctions in skills utilized in interpreting is a good, practical illustration of that. It is not realistic to privilege one over the other – unless one is, say, a Pakistani Muslim who only wants to learn to read and understand Islamic texts. Even then, in study abroad, learning the dialect is useful for obvious reasons.

I’ll give you a story: A Pakistani student in Egypt once said to me (as many were wont to do) that he was only interested in the Arabic of reading and writing and wanted nothing to do with the debased dialect. So, at the end of a successful year studying that variety at the expense of the local dialect, he and an American colleague were celebrating the end of the year by visiting Khan al-Khalili. There, the Pakistani student’s wallet was stolen. Upon realizing this, he began to cry out:

لصّ لصّ

But no one in the market paid him any mind. The American student, however, did and began to cry out:

حرامي حرامي

At which, the good people of the Khan set off after the thief – as they do in Cairo – caught hold of him, and returned the wallet to its owner! They gave the thief a fair drubbing into the bargain, as they also do in Cairo!

In Lebanon, they call a sort of standard high ammiyya this: il-lahja l-bayḍa . More or less – the light dialect.

D

LikeLike

Another Khan al-Khalili anecdote, if I may:

One of the time I was in Egypt (Cairo West Airbase), I supported the US Central Command (aka “CENTCOM” in “military-speak”) during one of its joint combined training exercise (part of a series called “Bright Star”.

One day, an Egyptian liaison officer and I escorted a group of CENTCOM staffers on an excursion into Cairo. We entered Khan al-Khalili and wandered through different parts of the souq. None of the other Americans spoke Arabic. One of them tried his hand at bargaining with a merchant, whose young son interpreted (gamely, but roughly).

The merchant remained gracious and patient as the conversation became increasingly convoluted, but never tense or strained. The exasperated American waved me over to assist. After the merchant and I exchanged respective salaams and formulaic amenities, we started our “inkesaar” discussion of the price-range for the item of interest to the American.

After a minute, the merchant stood up, waved sideways at the other shopkeepers listening nearby to gather around. Then he turned and pointed toward me and said in a loud voice: “Aii daa? Kalaamak min al-khaleej, wa wajjhek min al-shaam! Enta sheishanii? Daa ghareeb khalaS, wa Allahi…”

At that, the shopkeepers and passersby enjoyed a good and long laugh. The merchant was so amused by our conversation that he ultimately gave the item to the American, along with his best wishes and invitations to all to return there. (Mutshakereen ‘awii yaa beh… )

With warm memories and best regards to the gracious, endearing and enduring people of Egypt.. illi yeshrib min al-niil, laazim yerj3…

Regards,

Stephen H. Franke

LikeLike

Great article!!!

After having studied in Lebanon, Oman, Palestine and Egypt my Arabic is actually fusha with different dialects – but in the end everyone understands. So I totally second your approach!

Do you think having conversations in fusha are helpful? Still didn’t figure that out..

LikeLike

Stephen,

Much appreciate your insights.

You are so correct about figuring out what the proper protocol is and its an interesting topic. To not address people in the Gulf by their proper titles is in essence a sign of political disrespect. If one is trying to conduct business there it can be a strategic disaster.

However, in my experience, it’s not just Westerners who fail to do that. I have seen Egyptians or Lebanese who don’t bother to learn the right titles, usually out of a sense that they are somehow above that politically. If one wants to operate in Saudi Arabia, or any other monarchy, they have to learn the specific titles. For example, if one says “Hadarat Al Ameer” Egyptian-style, it’s just wrong. In fact, I would say that is more of a party foul for an Egyptian or a Lebanese person, who knows Arabic and would be expected to figure out the correct term, to do that, than an Western, who doesn’t, to completey botch a title.

David,

Agreed. Couldn’t agree more. I hope I wasn’t suggesting otherwise in the post.

Mathias,

Glad you liked the post. I do personally think having conversations in Fusha are helpful (I think they are more fun too).

My philosophy is that people should speak whatever they need to speak to get done whatever they want to get done.

I always hear people say “but that’s so wierd to talk in Fusha on the street.” However, as a non-native speaker, you aren’t expected to follow the same language rules as native speakers. If someone develops perfect practical Fusha, I can’t imagine any situation where native Arabic speakers in any Arab country, would say “that is so weird and ackward.” Instead, they are going to say “Wow, that is super impressive that you came here and learned at that level. I wish our young native Arabic speakers were as serious as you.”

Nathan

LikeLike

This is amazingly helpful. I really appreciate the comments about the differences between amiya and fus-ha and how they are perceived from non-native speakers. I’ve been studying Arabic in Maine, and speak comfortably in modern standard now- but I feel a little awkward about the fact that I don’t speak any dialect. All the Arabic speakers I know default to speaking to me in fus-ha/standard.

There is clearly this trend in US university education to prioritize amiya, yet the unspoken messaging I get from native Arabic speakers is that it is more polite or more appropriate for me, as a learner, to speak standard. Ekendall’s comment really helps me understand why: the opportunity for picking the wrong register is high as a learner, and so it’s probably better to aim for fus-ha/standard (I wish there were a better word to describe this register: fus-ha, but without all the case endings.)

LikeLike

Brook,

I’d put it this way: there is the perfect ideal of what students should speak if they have unlimited time to study the language. Then on the other hand, there is the practical desire to maximize the ROI from a career skills perspective, which, for most students means a limited period of time studying intensively, to be followed, by those who make it more of a priority, by informal study, on the side, with some job being the main occupier of their time.

I think my strategy #1 of picking a hybrid of something like 60% Formal Fusha and 40% one or more colloquials is a reasonable middle ground between the two.

Never apologize for speaking Fusha! Of course, as you progress with your studies, it is important to learn some Dialect. Virtually everyone you speak to will understand Formal. However, not all will be able to communicate to you that way. So therefore, as you are aware, having command of both is important.

Nathan

LikeLike

Thanks Nathan and everyone for insightful posts.

I would like to add that I definitely agree that a student doing a BA in Arabic has to be able to converse in a good level of a chosen dialect and in MSA mixed with some dialectal elements in more formal situations. They should also be able to write in the dialect when chatting with friends on social media apps for example and write in MSA (avoiding dialectal elements as much as possible) when carrying out formal/work-related tasks such as translations and business letters.

I think students usually gravitate towards a specific dialect for various reasons and regardless of what that dialect is, they should not be expected to speak more than one dialect fluently. I wonder why did you feel inclined to change your Egyptian dialect into Saudi and then to Levantine? Native speakers tend to stick to their dialects usually and in inter-dialectal conversations they may avoid some very localised words in their own dialects or borrow few elements from MSA. They can also borrow from the interlocutors’ dialects but the majority do speak in their own native dialect.

Although, I believe that students do not need to learn more than one dialect, I believe that they need to have awareness of the linguistic features of other dialects in order to better comprehend them.

Rasha Soliman

LikeLike

Hi Rasha, Good to hear from you! Interesting comment; “Native speakers tend to stick to their dialects … in inter-dialectal conversations” I wonder if that effect holds only for native speakers of Arabic (or any language) who remain mostly in their home environment or, if living abroad, who remain more or less in their own communities? My reason for asking is that I came across a man speaking an extraordinarily mixed dialect between Egyptian Arabic and Lebanese Arabic. I was in a barber’s chair, and he was sitting behind me, so I couldn’t see him. When the haircut was over, I turned round to engage him in conversation, and he looked Egyptian. That in itself doesn’t say much, because there are Egyptians who look Levantine and Levantines who look Egyptian. There has been a lot intermixing of Mediterranean populations for millennia. Turns out that he was from Alexandria but had been living with his Lebanese wife in Beirut for 25 years.

LikeLike

Pingback: So you want to read in Arabic? – arabicbooksculture

Pingback: Language Learning without Immersion – Brook DeLorme

Pingback: Language Hack 6: Uncomfortable Situations – Change Writer

Pingback: Reader Mail: 5 questions from an Arabic student in Cairo – Real World Arabic

Pingback: Managing in Arabic in Morocco – part 1 – Real World Arabic

Reblogged this on Nathan Field.

LikeLike

Pingback: 20 strategies for becoming a fluent Arabic speaker | Indran´s Arabic Notebook

This is the best blog I’ve come across for learning and maintaining Arabic proficiency. I am currently 3/3/2+ and practice Arabic every day. My daily routine is here https://soulofleisure.com/arabic-language-fluency/ I love the language and always try to get better every day.

LikeLike

Pingback: “20 Strategies for becoming a high-level Arabic speaker”